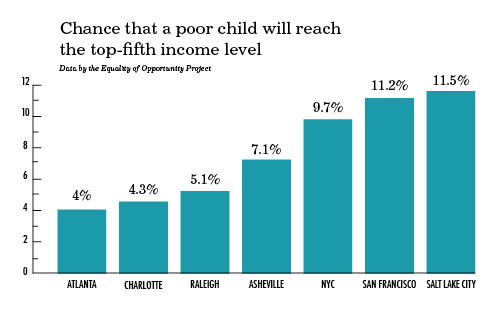

In Asheville, a child born to poor parents has a slim chance of making it into the top-fifth income bracket in America — just 7.1 percent. Those are better odds than an Atlanta-born child (4 percent) but far below U.S. cities with the best income mobility, such as Salt Lake City, Utah (11.5 percent), or Boston, Mass. (9.8 percent).

The ratings come from the Equality of Opportunity Project, a Harvard University and University of California at Berkley study recently featured in The New York Times. The report measures mobility by calculating the chances that a child born in the bottom-fifth income bracket can reach the top-fifth as an adult.

Most of the Southeast rates are low, showing up as a swath of deep red in the Times’ interactive map of the data. A closer look at the data indicates that two North Carolina cities — Raleigh and Charlotte — rank in the bottom 10 of 50 major U.S. cities. A Raleigh child has a 5.2 percent chance of moving up, while a Charlotte child has a 4.3 percent chance (Atlanta, Ga., ranks lowest). For comparison, bankrupt and economically beleaguered Detroit has a 5.1 percent mobility rate for poor children.

“The United States has historically been viewed as the ‘land of opportunity,’ a society in which a child's chances of succeeding do not depend heavily on her parents' income or circumstances,” study authors wrote in their summary. “But there is growing evidence that intergenerational income mobility in the U.S. is actually lower than in many other developed countries.”

Researchers cautioned that while they discovered strong correlations about why income mobility is so low in some areas but not in others, the exact causes are not clear. American cities and regions with better income mobility show higher rates of stable families, mixed-income neighborhoods, public infrastructure, strong schools and active civic or religious engagement, researchers noted.

The Times also observed that mobile and non-mobile areas aren't easily split by (or explained by) politics: Conservative stronghold Salt Lake City, Utah, and liberal bastion San Francisco, Calif. are two of the most income-mobile cities in the country, where children born into the lowest rungs have an 11 percent or better chance of rising to the top. It’s a mixed bag politically for the least mobile U.S. cities, too, from Cleveland, Ohio, to Detroit, Mich.

“What this study tells us is that where you live matters,” says Tazra Mitchell, a fellow with the North Carolina Budget and Tax Center, a progressive think tank that has researched income inequality and social mobility in the state. She identifies one reason North Carolina has low rates: Much of its employment growth has been in low-wage jobs unlikely to offer a way up, while higher-paying manufacturing jobs have disappeared.

“Even if you work as hard as you can, [and] do all the right things, there are still things that factor in your ability to achieve the American dream. It's not what we were taught when we were younger — that it's all hard work and ingenuity.”

Noting the differences across North Carolina, she points out that Charlotte has more areas with concentrated poverty, while Asheville has more mixed-income neighborhoods.

“There are lasting disadvantages [for] children who grow up poor,” Mitchell says. “You're more likely to have low-quality schools, [and] you're more likely to have poor health outcomes. [Areas of concentrated poverty] are more likely to have crime. That hurts children's ability to climb the economic ladder.”

Other factors include a high cost of living in the metro area, and the fact that many Asheville workers have low-wage jobs, Mitchell notes.

“We've transitioned from high-wage jobs to low-wage jobs, and that's fueling income inequality across the state,” she continues. “Wages are failing to keep pace with productivity growth during the recovery. We should think about what these low-wage jobs mean. Should we raise the minimum wage? Should we change our tax policy?”

The Asheville area’s high cost of housing combines with stagnant wages to make things precarious for many low-income families, says Greg Borom, advocacy director of local nonprofit Children First/Communities in Schools of Buncombe County, which fights childhood poverty.

“Housing is one of our community’s biggest strains for families,” he says. “Our housing market grew a lot faster than wages did. Those kind of expenses really make it difficult for families to meet their basic needs.” Pre-recession, the area still had its issues, Borom says, with 20 percent of children in poverty even in more prosperous years (now it's closer to 25 percent).

“I think it speaks to all the families here that are right on the cusp,” he says. Even where there's a good education system, “success depends on how stable things are at home.”

Also, rural areas have seen far less recovery than cities. The Asheville metro area includes the less urban Buncombe, Haywood, Madison and Henderson counties. The rural areas are less likely to have access to public infrastructure (if it exists) and less likely to have a “robust safety net.”

One other correlation highlighted by the study, and one Mitchell emphasizes, is tax policy. In North Carolina, she says, “low-wage workers pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes compared to the upper income.”

Mitchell concludes, “Income inequality is harmful to families and it threatens economic growth. More unequal societies enjoy shorter periods of growth, so this stuff really matters.”

In the trenches

One factor that may give Asheville higher mobility than some other cities is its extensive network of social-aid nonprofits. The YWCA and Children First are major players on that front. Both organizations offer an array of services for low-income families, including early childhood education, nutrition, resource centers and rent assistance. Both also help to coordinate and connect services with other nonprofits and government agencies.

“If you can have child care for your kid, you can go to work,” says Beth Maczka, YWCA executive director. “If their kid's getting a good educational start in our center, they're going to be ready for kindergarten. We have 19 kids going to kindergarten this year, and half of them are already reading; they beat the odds in our childcare center.”

“These programs definitely help to stem the tide a bit,” Borom agrees.

But such programs are on fragile ground, as state and federal cuts are creating “a ripple effect” for many agencies, says Borom, making it difficult to continue delivering services that could improve mobility, especially at an early age.

Maczka is witnessing a similar problem. “It's death by a thousand cuts,” she says. “It's not any one thing at one time. If one program went away, we'd close ranks, but if we're losing significant chunks of all our program, it makes it much more complicated to provide these services.”

She says that it also hampers successful programs. For example, YWCA's MotherLove program helps teen mothers stay in school and graduate, but it can only help 30 mothers a year. While all the mothers in the program have gone on to graduate, there isn’t enough funding to expand it. “It's sad, because that's where you stop poverty, it's these community programs that really support the most needy families.”

“We've been here 107 years,” says Maczka. “We can weather it a lot more than some of the smaller nonprofits; I'm really worried about them. [Losing them] will be a loss, because those groups are more grassroots and in the neighborhoods. We're really unraveling the fabric of our community.”

Beyond volunteering directly, which both organizations welcome, it’s essential that citizens advocate for better policies for making Asheville — or any city — a place where more born into poverty have a chance to reach the top, Borom asserts.

“There's an effort to change the broader message around what it takes to make children thrive,” he says. “How do we turn the tide against what's become the status quo in Buncombe County?”

For more information, go to the New York Times article, “In Climbing Income Ladder, Location Matters” at http://avl.mx/yd or the Equality of Opportunity Project at http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.